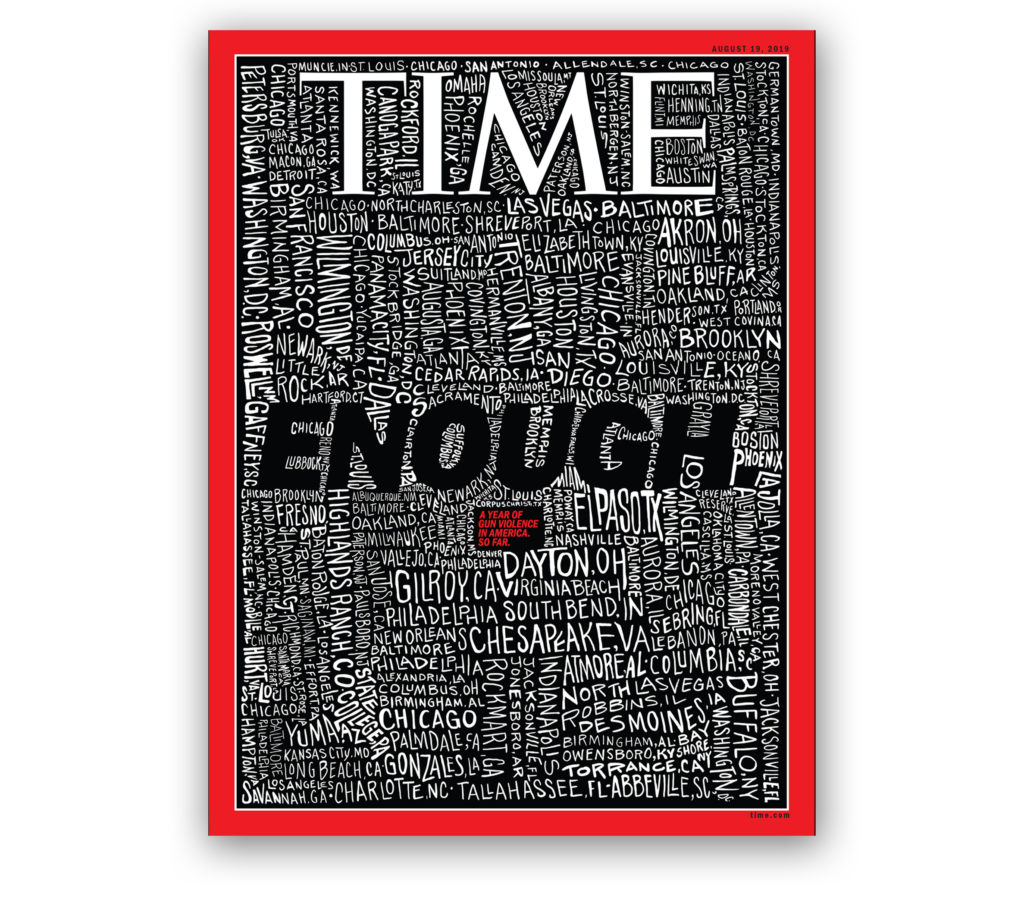

Words When Pictures Fail

A constant struggle for editorial artists is the search for a way to capture the essence of a story in a single powerful image. Unfortunately, picturing a semiautomatic assault weapon, as sinister as it looks, no longer shocks readers. In fact, guns and even images of crying survivors of mass killings feel cynically banal. That’s why this week’s Time Magazine cover stopped us in our tracks. San Francisco Bay Area artist John Mavroudis simply hand-lettered the 253 locations of mass shootings in America so far this year and added the word “ENOUGH.” The crude lettering is crammed onto the page with city names shown vertically, sideways and at a slant in large letters and small, filling every nook and cranny. Mavroudis calls his drawing “a frightening portrait of a country drowning in gun violence.” Indeed, the effect is chilling and memorable and gives perspective to our epidemic of domestic terrorism.